Cyclooctatetraene

| Cyclooctatetraene | |

|---|---|

| |

| IUPAC name | 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene |

| Other names | COT, [8]-annulene |

| Identifiers | |

| InChI | InChI=1/C8H8/c1-2-4-6-8-7-5-3- 1/h1-8H/b2-1-,3-1-,4-2-,5-3-,6 -4-,7-5-,8-6-,8-7- |

| InChIKey | KDUIUFJBNGTBMD-BONZMOEMBR |

| Standard InChI | InChI=1S/C8H8/c1-2-4-6-8-7-5- 3-1/h1-8H/b2-1-,3-1-,4-2-,5-3-, 6-4-,7-5-,8-6-,8-7- |

| Standard InChIKey | KDUIUFJBNGTBMD-BONZMOEMSA-N |

| CAS number | [] |

| EC number | |

| UN number | 2358 |

| RTECS | CY1400000 |

| ChemSpider | |

| SMILES | |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | C8H8 |

| Molar mass | 104.15 g/mol |

| Appearance | Clear yellow |

| Density | 0.9250 g/cm3, liquid |

| Melting point |

–5 °C to –3 °C (268–270 K) |

| Boiling point |

142–143 °C (415–416 K) |

| Solubility in water | immiscible |

| Hazards | |

| EU index number | not listed |

| Flash point | –11 °C |

| Autoignition temp. | 561 °C |

| Related compounds | |

| Other annulenes | Benzene [10]Annulene |

| Other compounds | Cyclooctane Tetraphenylene |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) | |

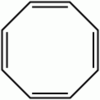

1,3,5,7-Cyclooctatetraene (COT) is an unsaturated derivative of cyclooctane, with the formula C8H8. It is also known as [8]annulene. This polyunsaturated hydrocarbon is a colorless to light yellow flammable liquid at room temperature. Because of its stoichiometric relationship to benzene, COT has been the subject of much research and some controversy.

Unlike benzene, C6H6, however, cyclooctatetraene, C8H8, is not aromatic. Its reactivity is characteristic of an ordinary polyene, i.e. it undergoes addition reactions. Benzene, by contrast, characteristically undergoes substitution reactions, not additions.

Contents

History

Cyclooctatetraene was initially synthesized by Richard Willstätter at Munich in 1905.[1][2]

Willstätter noted that the compound did not exhibit the expected aromaticity. Between 1939 and 1943, chemists throughout the US unsuccessfully attempted to synthesize COT. They rationalized their lack of success with the conclusion that Willstätter had not actually synthesized the compound but instead its isomer, styrene. Willstätter responded to these reviews in his autobiography, where he noted that the American chemists were 'untroubled' by the reduction of his cyclooctatetraene to cyclooctane (a reaction impossible for styrene). In 1947, Walter Reppe at Ludwigshafen at last repeated Willstätter's synthesis.[3]

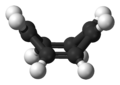

Structure and Bonding

Early studies demonstrated that COT did not display the chemistry of an aromatic compound,[4] yet early electron diffraction experiments concluded that the C–C bond distances were identical.[5] However, X-Ray diffraction data from H.S. Kaufman demonstrated cyclooctatetraene to contain two distinct C–C bond distances.[6] This result indicated that COT has fixed alternating single and double C–C bonds. In its normal state, cyclooctatetraene is non-planar and adopts a tub conformation with angles C=C–C = 126.1° and C=C–H = 117.6°.[7]

Chemistry

Richard Willstätter's original synthesis (4 consecutive elimination reactions on a cycloctane framework) gives relatively low yields. Reppe's synthesis, which involves treating acetylene at high pressure with a warm mixture of nickel cyanide and calcium carbide, was much better, with chemical yields near 90%.[3]

Because COT is unstable and easily forms explosive organic peroxides, a small amount of hydroquinone is usually added to commercially available material. Testing for peroxides is advised when using a previously opened bottle; white crystals around the neck of the bottle may be composed of the peroxide, which may explode when mechanically disturbed.

The π-bonds in COT react as usual for olefins, rather than as aromatic ring systems. Mono- and polyepoxides can be generated by reaction of COT with peroxy acids or with dimethyldioxirane. Various other addition reactions are also known. Furthermore, polyacetylene can been synthesized via the ring-opening polymerization of cyclooctatetraene.[8] COT itself —and also analogs with side-chains— have been used as metal ligands and in sandwich compounds.

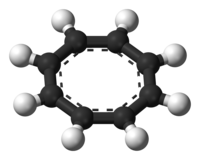

Cyclooctatetraenide dianion

COT readily reacts with potassium metal to form the salt K2COT, which contains the dianion C8H82−.[9] The dianion is both planar in shape and aromatic with a Huckel electron count of 10. Cyclooctatetraene forms complexes with some metals, including yttrium and lanthanides. One-dimensional europium-COT sandwiches have been described as nanowires.[10] The sandwich compounds U(COT)2, or uranocene and Fe(COT)2, are known.

The compound Fe(COT)2, when refluxed in toluene with dimethyl sulfoxide and dimethoxyethane for 5 days, is found to form magnetite and crystalline carbon also containing carbon nanotubes.[11]

Because COT changes conformation between tub-shaped and planar with addition or subtraction of electrons, it could, in principle, be used to construct artificial muscles. Such devices have been contemplated to be makeable by grafting COT derivatives to a backbone of a suitable conducting polymer, which would supply or remove the reducing equivalents.[12]

Natural occurrence

Cyclooctatetraene has been isolated from certain fungi.[13]

See also

- Cyclobutadiene

- Semibullvalene, an isomer of cyclooctatetraene

References

- ↑ Mason, S. The Science and Humanism of Linus Pauling (1901-1994). Chem. Soc. Rev. 1997, 26 (1), 1.

- ↑ Willstätter, Richard; Waser, Ernst Über Cyclo-octatetraen. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1911, 44 (3), 3423–45. DOI: 10.1002/cber.191104403216

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Reppe, Walter; Schlichting, Otto; Klager, Karl; Toepel, Tim Cyclisierende Polymerisation von Acetylen I Über Cyclooctatetraen. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1948, 560 (1), 1–92. DOI: 10.1002/jlac.19485600102.

- ↑ Johnson, A. W. Sci. Progr. 1947, 506, 35.

- ↑ Bastiensen, O.; Hassel, O.; Langseth, A. The ‘Octa-Benzene’, Cyclo-octatetraene (C8H8). Nature 1947, 160, 128. DOI: 10.1038/160128a0.

- ↑ Kaufman, H. S.; Fankuchen, I.; Mark, H. Structure of Cyclo-octatetraene. Nature 1948, 161, 165. DOI: 10.1038/161165a0.

- ↑ Thomas, P. M.; Weber, A. High resolution Raman spectroscopy of gases with laser sources. XIII - the pure rotational spectra of 1,3,5,7-cyclooctatetraene and 1,5-cyclooctadiene. J. Raman Spectr. 1978, 7 (6), 353–57. DOI: 10.1002/jrs.1250070614

- ↑ Moorhead, Eric J.; Wenzel, Anna G. Two Undergraduate Experiments in Organic Polymers: The Preparation of Polyacetylene and Telechelic Polyacetylene via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. J. Chem. Educ. 2009, 86 (8), 973.

- ↑ Katz, Thomas J. The cyclooctatetraenyl dianion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1960, 82 (14), 3784–85. DOI: 10.1021/ja01499a077.

- ↑ Nakajima JST Nanostructed Materials Project Highlights, <http://www.nanostruct-mater.jst.go.jp/highlights-e/2004/hilite_nakajima-01.html>.

- ↑ Walter, Erich C.; Beetz, Tobias; Sfeir, Matthew Y.; Brus, Louis E.; Steigerwald, Michael L. Crystalline Graphite from an Organometallic Solution-Phase Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128 (49), 15590–91. DOI: 10.1021/ja0666203.

- ↑ UCR Fiat Lux: Muscle building - UCR researchers hope to create artificial muscles, <http://www.fiatlux.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/display.cgi?id=469>.

- ↑ Stinson, M.; Ezra, D.; Hess, W. M.; Sears, J.; Strobel, G. An endophytic Gliocladium sp. of Eucryphia cordifolia producing selective volatile antimicrobial compounds. Plant Sci. 2003, 165, 913–22. DOI: 10.1016/S0168-9452(03)00299-1.

| Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination | |

This page was originally imported from Wikipedia, specifically this version of the article "Cyclooctatetraene". Please see the history page on Wikipedia for the original authors. This WikiChem article may have been modified since it was imported. It is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution–Share Alike 3.0 Unported license. |